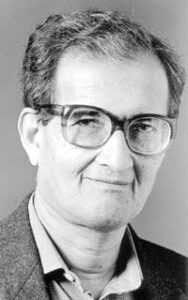

“India cannot get a salutation right now” because of its poor performance on healthcare, says world-renowned economist Amartya Sen.

“At the bottom of the world league”

India’s dismal track record on public healthcare puts it “at the bottom” of the world league, Sen remarked at an international conference in Mumbai in January. “It is disconcerting to note that despite being the world’s largest democracy, we are far from achieving reasonably good standards of healthcare delivery…even today”, he added.

Sen was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1998 and India’s highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, in 1999. He spoke on the topic, “Healthcare: A Commodity or Basic Human Need?” and took the opportunity to attack India’s politicians and press. He accused them of failing to initiate a public conversation on health.

Sen: India is “second last”

His speech was on the same weekend as calls came from the Population Foundation of India (PFI) to increase government spending on healthcare.

The PFI points out that India’s spending is less than that of the other BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa. These five countries are grouped together on the basis of their increasing economic expansion, industrialisation and geopolitical influence. They collectively account for around half of the world’s population and more than a fifth of its GDP.

India spends just 1.4 percent of its GDP on healthcare provided by the public sector. By contrast, China spends 3.1 percent; Russia 3.7 percent; Brazil 3.8 percent; and South Africa 4.2 percent. This is according to 2014 statistics published by the World Bank.

The PFI compares to India to other countries that are members of the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC). Sen also notes that, of the SAARC members, “six decades back India was second only to Sri Lanka, now it is second last, ahead only of Pakistan.” He observes, “Neighbouring countries…with similar or even lower income levels than India, have better health and social indicators.”

“A collective responsibility”

Sen accepts the importance of the private sector’s involvement. However, he emphasises that it will not be the panacea of India’s healthcare woes.

“No country has ever successfully provided universal health coverage without the strong support and commitment of the public health sector”, Sen says. To this end, he advocates “a higher proportion of GDP in healthcare, more recognition for the central role of public healthcare, better work ethics, along with the urgent need for efficient, sustainable initiatives.”

PFI’s executive director Poonam Muttreja concurs. She blames low health spending by the Indian government for “the growing inequities, insufficient access [to], and poor quality of, healthcare services.” She adds, “[planning] adequate and suitable opportunities to…address the health and well-being of this population” is “a collective responsibility” – one shouldered by “the government, civil society and other stakeholders.”

The Indian government is under mounting pressure to address the shortfalls of its healthcare system. Sen and the PFI are adding their voices to a growing chorus – one that includes the WHO and United Nations among them – who want India to act now. They recognise that much of its population lack adequate access to medicine. They also see that India cannot be the global power it is striving to be until the government addresses this problem.