Gujarat is expanding a number of prevention policies with the aim of making the state thalassemia free. Foremost among the proposed policies is the intention to make thalassemia testing mandatory for everyone, with a focus on testing women before they give birth.

Gujarat is expanding a number of prevention policies with the aim of making the state thalassemia free. Foremost among the proposed policies is the intention to make thalassemia testing mandatory for everyone, with a focus on testing women before they give birth.

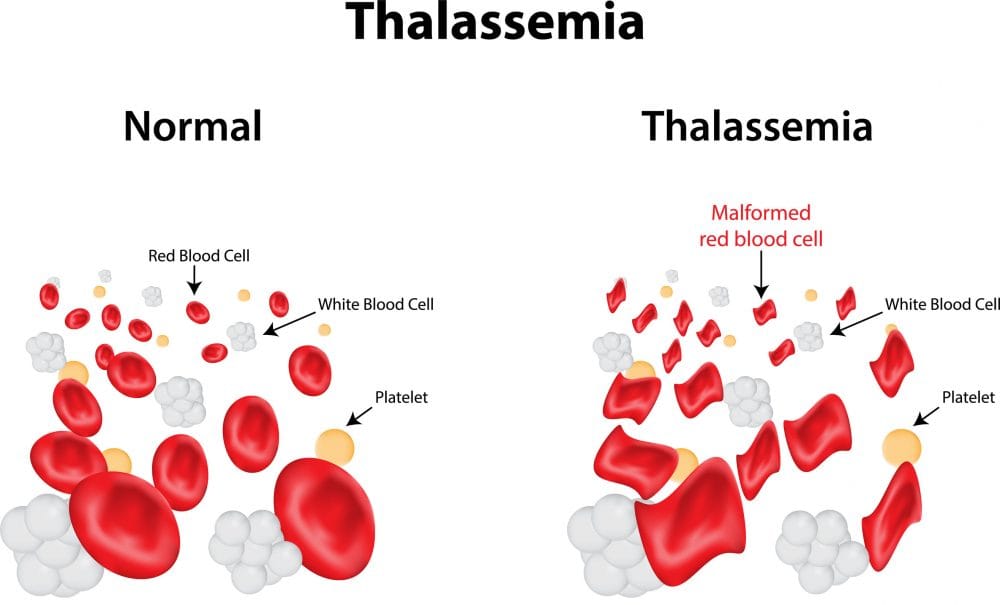

India is considered to be the world’s capital for thalassemia cases, with 10,000 new cases reported every year. As previously mentioned on Health Issues India (HII), thalassemia is a genetically inherited condition, with the genes involved related to the formation of globin, a molecule within haemoglobin (red blood cells). Improper function of haemoglobin can lead to reduced levels of oxygen circulating in the blood, which can have severe health implications, and is potentially fatal in its most severe form.

Suggestions to reduce the prevalence of thalassemia were put forward during a meeting to discuss the matter. Present at the meeting were Dr. Sudhir Parikh, publisher of News India Times and met Chief Minister of Gujarat, Vijay Rupani, on Aug. 10, in Gandhinagar. Chief Minister Rupani “agreed in principle” with the policy of making blood tests mandatory for all.

Gujarat is currently screening in Ahmedabad, Vadodara and Bhavnagar districts. Three lakh (300,000) pregnant women were tested in 2015 and 2016. During this time 186 pregnancies were terminated in which the child would have been born with thalassemia major. This is the most severe form of the disease in which the blood is almost entirely unable to transport oxygen. This would have likely resulted in the death of the children shortly following the birth.

The severity of the disease is variable, as noted previously by HII: The symptoms vary depending on how many genes are faulty or missing, ranging from one to four. The most severe case, in which a child has inherited four genes is referred to as thalassemia major.

Severity of the disease with three missing genes presents symptoms comparable to severe anaemia. As this is a condition present from birth, delayed growth and puberty is a common feature, osteoporosis is also a notable symptom.

With two genes missing, these same symptoms may be present in a less severe form. With only one missing gene there may be no symptoms at all. Of the treatments available, blood transfusion is the most common, though this will need to be a sustained treatment across the person’s life and can lead to iron overload and infection. A person with fewer affected genes and less severe symptoms is referred to as having thalassemia minor.

Couples which possess one or two faulty genes (thalassemia minor), have the potential to have a child who is free of thalassemia, has thalassemia minor, or thalassemia major. “It is not necessary that thalassemia-major couples can’t conceive a healthy child. But it is important they go for screening and ensure that their child is normal,” says Prakash Parmar of the Indian Red Cross Society (Gujarat). Parmar was part of the committee that drafted the national policy on hemoglobinopathies, in which Gujarat was designated as a testing ground for the thalassemia prevention strategies.

The strategy of mass blood tests may prove to be an effective method of reducing thalassemia numbers in India. This, coupled with scanning and family planning services could, as Parmar says, allow for those with minor versions of the disease to have healthy children. An increase in funding and accessibility of family planning services will however be vital for this plan to be effective.