Deadlines to eliminate kala-azar by the end of 2017, set out in the National Health Policy 2017, have not been accomplished.

The disease is proving difficult to eliminate, probably because of uneven usage of surveillance techniques across the country. By not effectively monitoring areas deemed to be at risk, any outbreak has sufficient time to spread. Surveillance coupled with effective and rapid delivery of treatment is vital to ensure outbreaks are contained.

India has considerably reduced the prevalence of kala-azar over recent years. Numbers continue to fall, but in order to be considered eliminated the disease prevalence has to be reduced to below one case per 10,000 people. Prevalence rates are higher than this in some localised areas.

In 2016, 94 blocks across the four endemic states were above the elimination rate of one case per 10,000 population. By the end of 2017, that number is expected to be reduced to 80, according to the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme. This means that yet another established deadline for the elimination of the disease has been missed. New infections continue to occur often enough that regular outbreaks are still problematic.

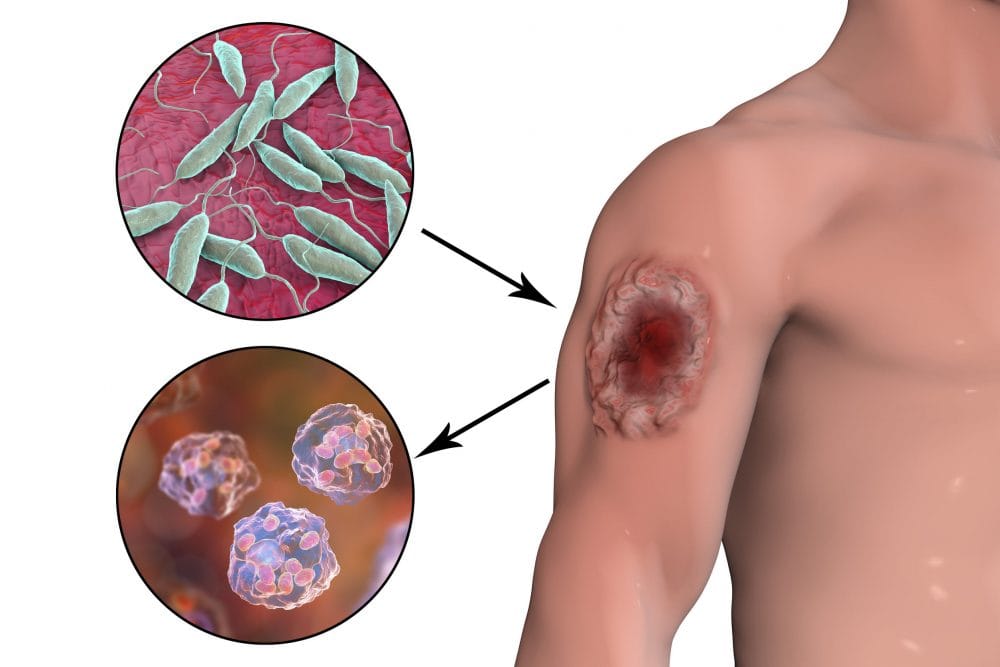

Relative ease of transmission between humans occurs due to the nature of the cause of kala-azar. Also called visceral leishmaniasis, the disease is caused by an infection by protozoan parasites from any of more than twenty leishmania species. The parasites are transmitted between humans via female sandflies, meaning the disease is endemic to any regions that may contain this species of fly.

Kala-azar can be treated however, even after symptoms subside, the infected individual is still at risk of developing post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL). This occurs when the parasites migrate to inhabit the individual’s skin cells. Though this form of the disease is not fatal, and proves little risk to the infected individual, it does allow them to act as a reservoir for the infection.

An individual with PKDL may again be bitten by a sandfly. This presents the kala-azar causing parasites an opportunity to infect the fly, this in turn allows for more human hosts to be infected upon further bites by the sandfly. In this manner even a single individual infected with kala-azar can cause an outbreak, making it difficult to ensure no new cases arise.

This is the latest in a series of failed elimination deadlines. In 2014 the then-Union Health Minister Harsh Vardhan claimed the disease would be eliminated by 2015. A previous deadline had been set for 2010. However, with each failed deadline the total number of cases of kala-azar has been gradually reduced. The implication of this is that, whilst elimination is within reach, previous targets have perhaps been too optimistic in their time frame.