“It was something that I had never expected, I was really shocked,” Nandita Venkatesan said as she recalled finding out she had become re-infected with tuberculosis (TB) in 2013. It was six years after she was first diagnosed with the disease in 2007, some months before her eighteenth birthday.

In a candid conversation profiled in The Lancet, Ms Venkatesan told journalist John Zaracostas about her experiences with TB and the stigma attached to the condition. A Mumbai native, Venkatesan required an eighteen-month course of medication to treat her initial TB infection. The re-infection, however, was more severe, having spread to the other organs. “It necessitated six surgeries including five done on an emergency basis to save my life“, said Venkatesan.

The re-infection and after-effects of a plethora of treatments led to Venkatesan experiencing depression. It left her bedbound for two years and caused her to lose hair, weight and even her hearing, the latter as a consequence of treatment with injections of the antibiotic kanamycin. Since her ordeal, however, Venkatesan has become an advocate for TB sufferers – hoping to counteract the stigma attached to the disease and help those struggling with the condition.

“A doctor had told me not to inform anyone about it and to just keep it with my family and inform one college professor,” she recalled, concerning her initial diagnosis. “So, being silent about it, I could see now, when I think in hindsight, it was slowly eating away into my self-esteem.”

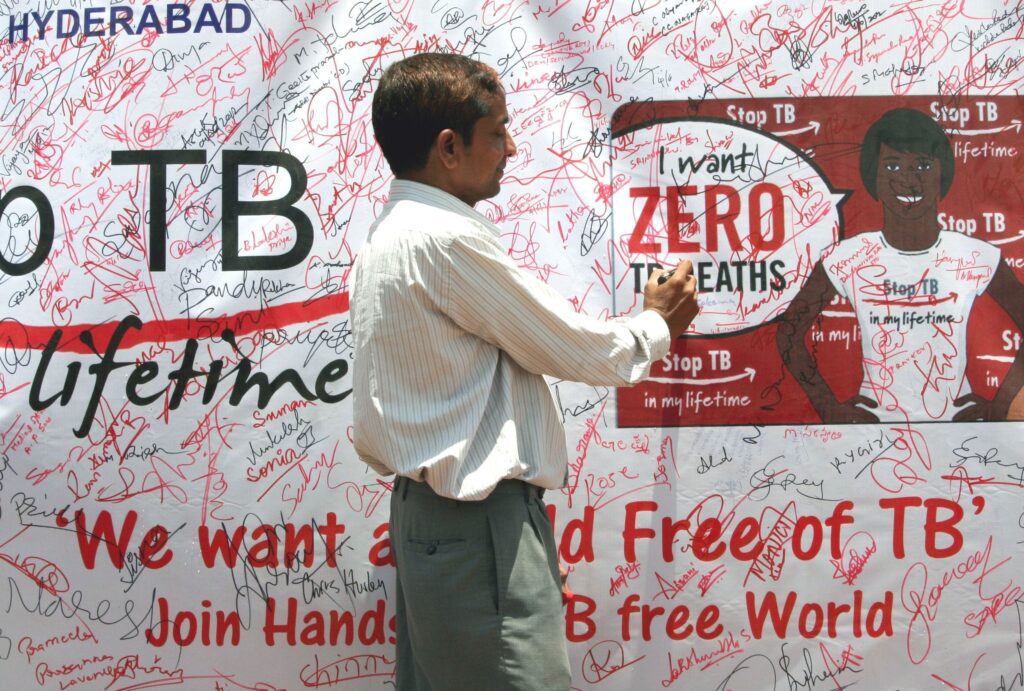

The exposure to this stigma inspired her, years later, to “speak up”. Venkatesan decided that not doing so would be doing “a great disservice to others because it was not the type of guidance I received when I was battling the illness”. Witnessing media reports about India’s high TB burden, Venkatesan saw that patients were seldom represented in the coverage – and, encouraged by one of the surgeons who treated, rose to the challenge.

In the years since, Venkatesan has campaigned on issues ranging from access to TB medications to patient safety to counselling for fellow TB survivors. She has advocated as a Tedx speaker an addressed world leaders at last year’s UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Ending TB. Her credo is that the voice of sufferers must play a vital role in informing policy. “Survivors bring to the table first-hand experience of ground realities, empathy, and a burning desire to shake the status quo. Use them, not think for us, without us,” was her message to the UN.

To this end, Venkatesan has sat this year on a Lancet Commission on TB, making her voice heard as experts today release guidelines on how tuberculosis can be eliminated within a generation. This is contingent upon high-burden countries possessing the will to act.

“Elimination of TB is feasible, but only if existing interventions are strengthened and improvements are made to the services that are currently available. In any case, the present rate of decline is grossly insufficient.”

Major reports were published earlier this month in The Lancet Global Health and by the journal’s Commission on Tuberculosis, ahead of World TB Day which is observed today. The reports make it clear that elimination of TB is feasible, but only if existing interventions are strengthened and improvements are made to the services that are currently available. In any case, the present rate of decline is grossly insufficient.

As highlighted in the Commission’s Report, India – as with other high-burden countries – is lagging far behind targets to reduce TB incidence by ninety percent and mortality by 95 percent between 2015 and 2035. At the current rate of decline, India is set to meet the targets by 2124 – almost a century after target.

The vitality of India’s leadership in the global fight against TB cannot be understated. India accounts for 27.3 percent of the global TB burden. In 2017, 421,000 Indians lost their lives to the disease – the highest TB death toll of any country in the world. Yet, despite TB lingering at the forefront of the public health discourse as a major threat, the report card afforded India by the Lancet Commission gives a decidedly mixed set of results.

Prime Minister's Office (GODL-India) [GODL-India (https://data.gov.in/sites/default/files/Gazette_Notification_OGDL.pdf)]

“India needs improvement on most of the indicators necessary to make the accelerated push against TB enshrined into countries’ agendas”

The Commission states political will against TB in India is high. However, it nonetheless notes that India needs improvement on most of the indicators necessary to make the accelerated push against TB enshrined into countries’ agendas at last year’s High-Level Meeting. In particular, India falls short when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of those with drug-sensitive and multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB). India’s progress on both indicators ‘[needs] improvement’ according to the report card.

Access to healthcare remains a significant challenge. The report highlights low state-provided financing of India’s public health system, translating to high levels of catastrophic expenditure paid by TB patients out-of-pocket. This combination poses a barrier to diagnosis and treatment of TB cases, as observed with cases of drug-sensitive TB and MDR-TB as highlighted above.

This issue emphasises the need for paying attention to patients’ experiences and the daily reality of many of India’s TB sufferers. Treatment, if only available from the private sector, can rapidly become unaffordable – heightening the importance of engagement with the private sector to bring down costs and investing into the public sector to make treatment more readily available from state-run services. The Lancet report highlights that the number of patients reliant on the private sector is a major loss when it comes to the TB ‘care cascade’ – referring to the sequential packages of treatments and interventions TB patients undergo.

“Of the 2.74 million TB patients who fell ill in 2017, 34 percent were either undiagnosed or not told about their condition”

Further highlighting the issue is the fact that, of 2.74 million TB patients who fell ill in 2017, 34 percent were either undiagnosed or not told about their condition. This is alarming – not only because it prevents TB patients from availing timely treatment, but because it also furthers the risk that the condition, if undetected in patients, can go on to be spread among communities.

Exacerbating India’s TB burden is the profound impact of aggravating factors. These range from relatively high levels of tobacco use to a burgeoning diabetes epidemic to catastrophic levels of pollution to a substantial burden of HIV.

Progress against these factors as noted by the report card is variable. India scores well on tobacco control measures such as taxation, but is in need of improvement when it comes to addressing other factors such as air pollution and providing antiretroviral therapy to those suffering from HIV. TB is the most common illness presenting in those with HIV and is a major cause of deaths related to the disease.

It should be noted that India’s political commitment towards ending TB is not for want of articulation. Indeed, a comment provided for the Commission’s report by India’s Union Minister for Health and Family Welfare J. P. Nadda reaffirms the central government’s will to make TB a thing of the past in India.

“‘Existing tools to fight tuberculosis must reach all those in need and better tools must also be developed. Drivers of tuberculosis, such as rapid urbanisation, overcrowding, diabetes, and undernutrition, are challenges that need to be addressed'”

– J. P. Nadda

“Tuberculosis not only exacts a terrible mortality toll in India, it also has profound financial implications,” the Minister writes. “As the Commission’s analysis shows, tuberculosis in India keeps people from climbing out of poverty for 7 years after they have completed tuberculosis treatment.”

To respond to such challenges, Mr Nadda emphasises acts taken by the central government. Efforts to increase case detection, engagement with the private sector, and efforts to support TB patients in key areas such as nutrition are among those touted by the Minister, who asserts these efforts are bearing fruit. “The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is implementing active tuberculosis case-finding campaigns. So far, the campaign has covered 447 districts, screened more than 144 million people at risk of the disease, and detected more than 50000 additional tuberculosis cases,” he states.

Whether existing interventions and policies are enough to realise ambitions of ending TB in India by 2025, however, is a different story. This much Mr Nadda acknowledges.

“I am aware of the challenges to end tuberculosis in a large and diverse country like India,” he says. “Existing tools to fight tuberculosis must reach all those in need and better tools must also be developed. Drivers of tuberculosis, such as rapid urbanisation, overcrowding, diabetes, and undernutrition, are challenges that need to be addressed.”

“India is unlikely to meet global TB targets by 2025 – never mind making it a thing of the past altogether”

The central government is rising to this challenge, Mr Nadda maintains. As such, “India serves as a model to the global community of how political leadership can lead to substantial investments that result in programmatic and potential epidemiological changes.” However, it is clear from the Commission and the Lancet Global Health report that more needs to be done. With the present range of interventions, the report warns, India is unlikely to meet global TB targets by 2025 – never mind making it a thing of the past altogether.

This must take on board the Commission’s recommendations for India, one informed by experts and survivors like Ms Venkatesan. Such measures include expanding access to TB treatment and services; increasing government spending on health; fully funding the national TB program through such increased expenditure; and affirming the commitment to global targets through concrete policy objectives.

What must be remembered in all of this belying statistics and political commitments is a wealth of human tragedy, frustrated by stigma and shortfalls in the public health system. Ensuring that the wellbeing of patients is paramount will play a centric role in making sure that, in years to come, the TB burden is addressed properly and moving India towards the time it has long been aiming for, when TB – is as the Lancet Global Health notes, “a disease of antiquity” and is nothing more than that.

As Ms Venkatesman makes clear, “if you don’t listen to someone’s first-hand suffering you’re not going to know how it feels to suffer all this pain”. It is, she says, “high time” that governments do so.

The Lancet Commission report and Global Health study can be accessed here.