Poisonous air is causing toxic damage to people across the world. Nine out of ten of us breathe polluted air. Now for the first time, a World Health Organisation (WHO) report has highlighted its damaging impact on child health and survival.

Over 93 percent of the world’s 1.8 billion children are exposed to toxic air pollution, the report attests. This includes 630 million under the age of five. 700,000 children under five die each year due to air pollution and more than a quarter of deaths of children under five years is directly or indirectly related to environmental risks.

“The main sources of air pollution may vary from urban to rural areas, but no area is, strictly speaking, safer”

The study shows that both outdoor and household air pollution contribute to respiratory tract infections that resulted in 543,000 deaths in children under 5 years in 2016.

Ambient air pollution (AAP) is primarily derived from anthropogenic processes, including fossil fuel combustion, industrial processes, waste incineration, agricultural practices, and natural processes such as wildfires, dust storms and volcanic eruptions.

The main sources of air pollution may vary from urban to rural areas, but no area is, strictly speaking, safer. AAP was responsible for 4.2 million premature deaths in 2016; of these, almost 300,000 were children under five years.

“Widespread dependence on solid fuels and kerosene for cooking, heating and lighting results in far too many children living in terribly polluted home environments”

Risks associated with breathing household air pollution (HAP) can be just as great. Widespread dependence on solid fuels and kerosene for cooking, heating and lighting results in far too many children living in terribly polluted home environments.

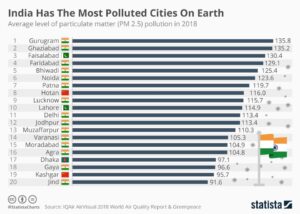

These are worrisome figures and should ring alarm bells for a country like India, home to seven of the world’s ten most polluted cities and where household air pollution contributes to between 22 and 52 percent of the overall pollution levels, according to a United Nations Environmental Programme study.

“There is compelling evidence of an association between air pollution and infant mortality”

The WHO guidelines discourage households from using kerosene and unprocessed coal because of the serious health hazards associated. Unfortunately, kerosene is still used for lighting by many of approximately one billion people who lack access to electricity.

The WHO’s report has incorporated several studies, conducted in the last ten years, to lay out the below-mentioned effects of air pollution on child health.

There is strong evidence that exposure to ambient pollution is associated with low birth weight. Maternal exposure is believed to increase the risk of preterm birth. One of the studies conducted in India gave an adjusted odds ratio of 1 : 43 for preterm birth in houses in which solid fuel is used as compared with those in which liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) or kerosene is used.

There is compelling evidence of an association between air pollution and infant mortality. The findings indicate that maternal exposure to PM2.5 should be considered with other risk factors for low birthweight in India.

“The findings include positive associations between exposure to air pollution in utero and postnatal weight gain or attained body mass index, and an association has been reported between traffic-related air pollution and insulin resistance in children.”

Both prenatal and postnatal exposure to air pollution can affect neurodevelopment, lead to lower cognitive test outcomes and influence the development of neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The findings include positive associations between exposure to air pollution in utero and postnatal weight gain or attained body mass index, and an association has been reported between traffic-related air pollution and insulin resistance in children.

“Reducing AAP requires wider action, as individual protective measures are not only insufficient, but neither sustainable nor equitable”

Studies have found compelling evidence that prenatal exposure to air pollution is associated with impairment of lung development and lung function in childhood. Studies have also found associations between prenatal exposure to AAP and higher risk of retinoblastomas and leukaemia in children.

In the end, the study rests the responsibility of ‘lifting this lifelong burden’ on health professionals by informed collective action, equity and access. Protective measures such as the use of clean stoves for cooking may mitigate HAP and improve the health of the whole family; however, reducing AAP requires wider action, as individual protective measures are not only insufficient, but neither sustainable nor equitable.

The study can be accessed here

/2019/03/26/air-pollution-child-health/

http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/environment-food-and-rural-affairs-committee/joint-inquiry-into-improving-air-quality/written/73685.pdf