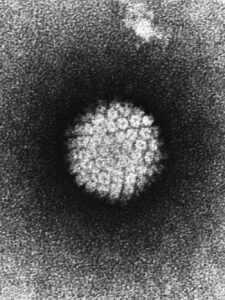

New research confirms again what public health experts have long asserted: vaccination against the human papillomavirus (HPV) is an effective tool in reducing the spread of cervical cancer. For India, the news is important. Given the high death toll of cervical cancer in the country, and stalled efforts to roll out HPV vaccination, the finding ought to serve as a call to action.

New research confirms again what public health experts have long asserted: vaccination against the human papillomavirus (HPV) is an effective tool in reducing the spread of cervical cancer. For India, the news is important. Given the high death toll of cervical cancer in the country, and stalled efforts to roll out HPV vaccination, the finding ought to serve as a call to action.

According to a study published in The Lancet, there is “compelling evidence of the substantial impact of HPV vaccination programmes on HPV infections and CIN2+ among girls and women.” CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) refers to the abnormal growth of cells on the cervix’s surface, which could be a precursor to the development of cervical cancer as the change observed in cells is potentially precancerous. CIN is graded between one and three in ascending order of abnormality.

Given the efficacy of the HPV vaccine in reducing the prevalence of these, the study states “our results provide strong evidence of HPV vaccination working to prevent cervical cancer in real-world settings.”

“Among girls and women aged thirteen to nineteen, the research showed that prevalence of infection with HPV-16 and HPV-18 – the two strains of the virus responsible for seventy percent of cervical cancer cases – dropped by 83 percent with HPV vaccination.”

Researchers assessed data from sixty million people, utilising data from 65 studies covering fourteen high-income countries (as a disclaimer, the authors note “there is a lack of data from low and middle-income countries…where the burden of disease is far greater than in high-income countries and results should be extrapolated to those countries with caution.”) The scope of the research encompassed a period of up to eight years following vaccination, analysing the efficacy of the vaccine in reducing HPV infections, CIN2+, and the development of anogenital warts. The research concluded that, following vaccination, prevalence of all three declined significantly.

In the case of anogenital warts, both females and males registered a decline in diagnoses across multiple age groups. In girls and women aged thirteen to nineteen, diagnoses fell by 67 percent; in women aged twenty to 24, diagnoses fell by 54 percent; and in women aged 25 to 29, diagnoses fell by 31 percent. In boys and men aged between fifteen and nineteen, diagnoses fell by 48 percent. In men aged twenty to 24, the reduction was 32 percent.

For HPV infections, the study produces similarly promising results. Among girls and women aged thirteen to nineteen, the research showed that prevalence of infection with HPV-16 and HPV-18 – the two strains of the virus responsible for seventy percent of cervical cancer cases – dropped by 83 percent with HPV vaccination. Among women aged twenty to 24, the prevalence of HPV-16 and HPV-18 infection dropped by 66 percent. Meanwhile, the prevalence of infection with HPV-31, HPV-33, and HPV-45 – also linked with the development of cancer – dropped by 54 percent in girls and women aged thirteen to nineteen. Finally, the prevalence of CIN2+ in girls and women aged thirteen to nineteen dropped by 54 percent; in women aged twenty to 24, prevalence dropped by 31 percent.

“The WHO call for action to eliminate cervical cancer may be possible in many countries if sufficient vaccination coverage can be achieved.”

The findings are of great relevance, particularly given what it tells us about the herd effect (referring to how large-scale immunisation within the population against infections such as HPV can protect those who are not immunised). Countries with high vaccination coverage across a broader demographic scope (referred to as multi-cohort vaccination, where a broader age range and both sexes are vaccinated) displayed significant reductions in the consequences HPV infections compared to those with lesser rates of coverage and where vaccinated groups were narrower in scope. “Programmes with multi-cohort vaccination and high vaccination coverage had a greater direct impact and herd effects,” the study states.

The study corroborates what has long been understood: the HPV vaccine saves lives. HPV is linked not only to cervical cancer, but also cancers of the anus, vagina, vulva, penis, mouth, and throat. A HPV vaccine that protects against nine strains of the virus could prevent ninety percent of HPV-related cancers worldwide.

A Lancet study highlighted the reality that HPV vaccination saves lives. As Health Issues India reported at the time

“Expanding prevention programmes such as vaccination against HPV in the next few years could avert thirteen million cervical cancer deaths. Moving towards HPV vaccine coverage of 80-100 percent within the next few decades has the potential to drive down cervical cancer rates to the extent that the disease would almost disappear as a public health threat by the end of the century – even in countries towards the bottom of the Human Development Index (HDI). In the process, millions of cancer cases would be prevented and millions of lives would be saved.”

“The landscape of HPV vaccination is rapidly changing, with several countries recently switching from three to two-dose schedules, gender-neutral vaccination, and a newer vaccine that targets more HPV types,” said Professor Marc Brisson of Canada’s Université Laval, who was a co-author of the study. “It will be crucial to continue monitoring the population-level impact of HPV vaccination to examine the full effect of these changes in strategies and quantify the effect of vaccination in low-income and middle-income countries.

“Because of our finding, we believe the WHO call for action to eliminate cervical cancer may be possible in many countries if sufficient vaccination coverage can be achieved.”

“432.2 million girls and women aged fifteen and above are at risk of developing the disease. It is believed that one in every 53 Indian women will develop the disease in their lifetime. Despite this, the HPV vaccine is yet to be included in the country’s Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP)”

The study carries massive implications for India. While the precise results of the research should not be extrapolated as the authors forewarn, it is yet another reminder of the value of the HPV vaccine as a weapon against cervical cancer – a disease which, in India, incurs a massive death toll. 67,500 Indian women lose their lives to the disease every year – a rate of one death every eight minutes. Cervical cancer accounts for seventeen percent of all deaths due to cancer in the nation.

Risk is high among India’s population. As previously reported by Health Issues India, 432.2 million girls and women aged fifteen and above are at risk of developing the disease. It is believed that one in every 53 Indian women will develop the disease in their lifetime.

Despite this, the HPV vaccine is yet to be included in the country’s Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP) despite the urging of health experts – at home and abroad. The reasons why have a lengthy history, dating back to a study conducted in 2009 concerning use of the HPV vaccine.

The research involved 23,500 participants, the majority of whom were girls aged fourteen to nineteen – predominantly of tribal populations. In the aftermath, seven of the participants who were administered doses of the HPV vaccine died, provoking outrage from policymakers; castigation of those involved in conducting the research including NGO PATH and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; and accusations of ethical violations.

The legacy of the scandal manifested in reluctance to roll out the HPV vaccine at the national level despite the vaccine’s proven benefits. Many took the deaths of seven young girls as indicative that the vaccine was hazardous to health. What was missing in the coverage of the deaths, however, was the fact that the causes of death were unrelated to the vaccine: pesticide poisoning accounted for two of the deaths, whilst others were respectively caused by drowning, a snakebite, and malaria. The other two deaths were due to a stroke and a fever. In both instances, investigative committees established that the HPV vaccine was not to blame.

Despite the lack of evidence as to hazards linked to the HPV vaccine, and its proven efficacy as a preventative measure against cervical cancer, political influencers and other interests have successfully intervened in preventing the Centre from facilitating its national rollout. This is no less than a national disgrace and represents a severe failing of governments past and present to act in the best interests of the health of India’s girls and women. The latest research reinforces the reality: it is time to vaccinate against HPV. To ignore this reality is to condemn millions to a preventable death.

The study, “HPV vaccination programmes have substantial impact in reducing HPV infections and precancerous cervical lesions”, can be accessed here.