The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued a report regarding India’s continued fight against visceral leishmaniasis — also known as kala-azar (KA).

Overall, the report praises India’s National Kala-Azar Elimination Programme (NKEP), noting the “the Government of India is committed to eliminating KA as a public health problem, and continued political, administrative, technical and partner support have put India on the verge of achieving the elimination target in 2021. Covering the last mile of elimination is therefore the main task of the NKEP.”

However, the situation regarding kala-azar in India is rife with mixed messages. On one hand, the disease is likely one of the closest to being considered eliminated in India, with the vast majority of areas in which the disease is prevalent already qualifying for the status of elimination — though, critically, not eradication. In sharp contrast to the optimism of the disease being close to elimination is the fact that this has been the case for more than a decade.

As Health Issues India reported at the time of the Union Health Budget 2017, “despite being the most likely to be eliminated, this target has been set and was not attained in previous announcements by the Indian government. In 2014…Health Minister Harsh Vardhan claimed the disease would be eliminated by 2015. Previous deadlines had been set for 2010.”

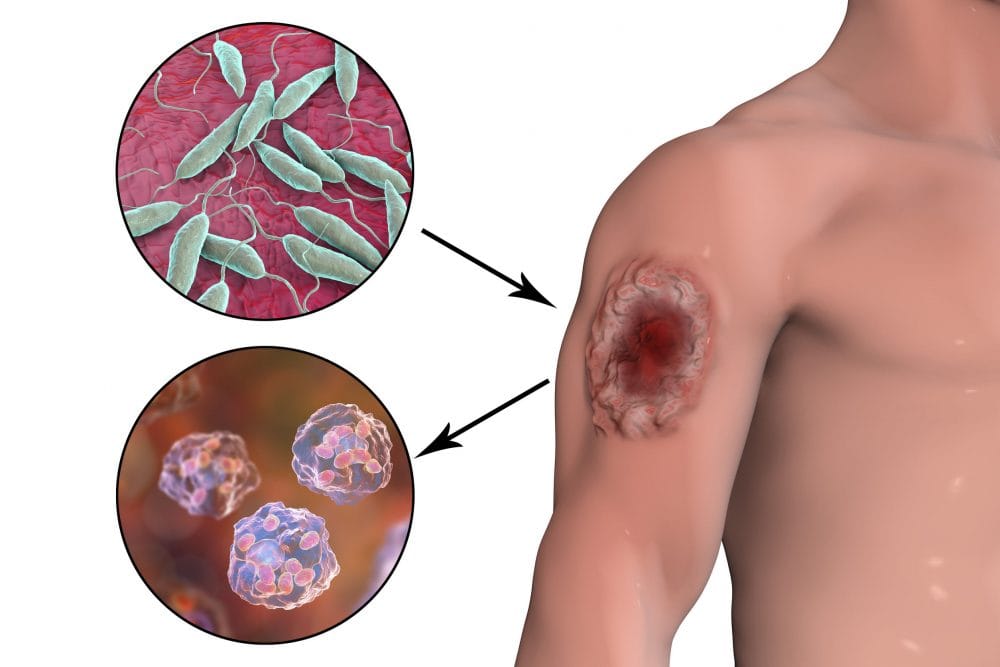

The distribution of kala-azar has been broken down by the WHO as follows; “cutaneous leishmaniasis is confined to the north-western part of the country ([Himachal] Pradesh, Rajasthan), whereas KA is endemic in four states, Bihar (33 districts, 458 blocks), Jharkhand (four districts, 33 blocks), West Bengal (eleven districts, 120 blocks) and Uttar Pradesh (six districts, 22 blocks), which contain approximately ten percent of the total population at risk in India (136.5 million). In Uttar Pradesh, five more districts are categorised as previously endemic. A few sporadic and imported cases are reported in other parts of [the] country (Assam, Delhi, Kerala, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand).”

“There are around 130 million people at risk of kala-azar in the 54 districts of four endemic States,” said Dr Neeraj Dhingra, director of the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme at the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, in a previous WHO report. “We have made substantial progress in reducing the endemicity of kala-azar by ensuring house to house search, treatment and follow up of cases. We are determined to eliminate the disease soon and counter the challenges of continued transmission in the country.”

Cases above the elimination threshold are now restricted to just six percent of districts. While effective treatment is available, detection is where India is falling behind. “…We’ve had weak reporting of relapsed cases, increased cases of post Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis and inadequate tools for vector surveillance. All these need to be addressed along with a reinforcement of the national task force to harmonise efforts by stakeholders and the ministry of health” said Dr Jorge Alvar, head of the mission who, in the past, led the global leishmaniasis elimination programme at the WHO.

The disease has shown to be easily treated, with clinical trials of amphotericin B showing an efficacy of around 99 percent. In order to actually move towards eradicating the diseases, however, India will need to mobilise a greater surveillance network, alongside a rollout of the medication.

India’s NKEP has shown a huge degree of success in reducing disease cases as a result of the availability of effective treatment. According to the report, “the number of KA cases has decreased by 97 percent (2,048 cases in 2020) since the start of intensified KA activities in 1992 (77,102 cases), and the number of deaths has been reduced from 1,419 in 1992 to 58 in 2018 and further decreases to 43 in 2019 and 37 in 2020 (provisional).”

The WHO report noted that “the [NKEP] must overcome operational challenges such as the quality of surveillance, IRS operations and engagement of private and rural health practitioners. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected programme implementation since early 2020; however, essential case management and vector control activities have been resumed. The impact of COVID-19 on NKEP is yet to be assessed.”

As with many other diseases kala-azar may have fallen into a lower priority placement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lack of surveillance during this time could allow for the disease to resurge and reclassify more districts into the above-elimination levels. Kala-azar is a perfect demonstration that when it comes to the eradication of diseases, it is often the final hurdle that proves to be the most difficult.