When monkeypox suddenly started spreading globally in May, the world was fortunate in one respect: A vaccine was available. MVA, originally developed by Bavarian Nordic as a smallpox vaccine, was already licensed for monkeypox in Canada and the United States (US). European Union (EU) regulators have since followed suit. Vaccine supplies are limited, and no doses have been shared with countries in Africa that have long been affected by monkeypox. But in Europe and North America, clinics have by now delivered thousands of doses to people in high-risk groups. www.science.org/content/article/how-effective-monkeypox-vaccine-scientists-scramble-clues-trials-ramp?

There’s little doubt the vaccine can help, but that’s about all that’s certain. Exactly how well MVA protects against monkeypox and for how long is not known. Nor is it clear how much protection is lost by giving just a single dose rather than the recommended two doses, as some countries are doing to stretch supply.

But the ethical and logistical complexities of the monkeypox crisis, which is overwhelmingly affecting men who have sex with men (MSM), are making these questions hard to answer. Placebo-controlled clinical trials are fraught because MVA is already licensed and people are clamouring to get it. And vaccine clinics are often set up at short notice as doses become available, making it harder to organize a trial and enrol subjects. Researchers are responding with a plethora of inventive trial designs.

MVA was licensed for monkeypox based on data from animal experiments and the immune response it triggers in humans. But its efficacy has barely been tested in people, and not at all for preventing sexual transmission, which results in “very significant mucosal exposure, which is not the same thing as just brushing up against somebody,” says Anne Rimoin, an epidemiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

So far, there’s scant data on how well the vaccine is working in the current outbreak. Among 276 individuals who received a shot at a Paris hospital as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after reporting a high-risk contact, 12 developed a monkeypox infection, French scientists reported in a recent preprint, 10 of them within 5 days of vaccination and two after more than 20 days. That some people would develop monkeypox a few days after being infected is not surprising, says Jade Ghosn of Bichat Hospital, who led the study. “The vaccine is not a miracle, it needs time to be effective.”

The study had no control group, however, making it impossible to tell how many people would have developed monkeypox if no one had been vaccinated. And people eager to be vaccinated may have lied about having had a high-risk contact. “That makes results from these studies on PEP really hard to evaluate,” says immunologist Leif Erik Sander of the Charité clinic in Berlin, who’s setting up a vaccine study in Germany.

////

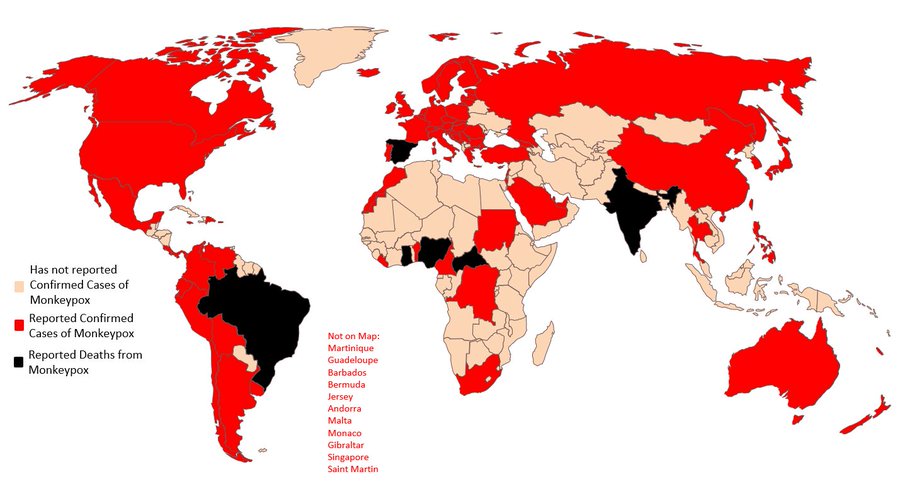

President Joe Biden’s administration last week designated the monkeypox outbreak a national public health emergency, allowing US health officials easier access to funds and procedural flexibility as they respond to rising cases (more than 8,900 as of 8 August). www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-south-korea-lunar-orbiter-us-monkeypox-response-lost-satellite?

Earlier in the week, the White House appointed Robert Fenton, a senior official at the Federal Emergency Management Agency, as national monkeypox response coordinator. Demetre Daskalakis, a physician who directs the Division of HIV Prevention at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, will serve as deputy coordinator. Daskalakis has experience working with the LGBTQ community; 97.5% of monkeypox cases with available data on sexual behaviour have been in men who have sex with men, according to a 3 August report from the World Health Organization. As Science went to press, the US had the world’s largest number of confirmed monkeypox cases.

/////

China’s financial hub Shanghai said on Sunday it would reopen all schools, including kindergartens, primary and middle schools on Sept. 1 after months of COVID-19 closures. The city will require all teachers and students to take nucleic acid tests for the coronavirus every day before leaving campus, the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission said. It also called for teachers and students to carry out a 14-day “self-health management” within the city ahead of the school reopening, the commission said in a statement.

Meanwhile, China reported more than 2,000 local COVID-19 cases on Friday as infections in the southern Hainan island edged higher despite stricter curbs imposed earlier this week. The southern province, a popular tourist destination, reported 1,426 cases. More than 1,230 of them were in the beach resort city of Sanya, where more restrictions were added on Thursday. Hainan’s authorities had aimed to eliminate community transmission by August 12.

////

The US Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) has announced that because the risk of “medically significant” COVID-19 has decreased, some overall public health measures the agency initially recommended may no longer be necessary. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/979109?src=wnl_edit_tpal&uac=398271FG&impID=4525875&faf=1

For example, CDC recommendations on social distancing, quarantining and testing children for COVID-19 while allowing them to stay in school — known as the test-to-stay strategy — may no longer be necessary for most Americans. The agency said high levels of immunity from vaccinations and prior infections, along with the availability of effective treatments and tools that prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, prompted the action.

However, the agency also said people who know they are high-risk for severe COVID-19 should continue to practise a multi-layered approach to keeping themselves safe. Well-known strategies include improved ventilation, well-fitting masks and testing as warranted.

The new CDC guidance was published today in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

////

Polio outbreaks incited regular panics decades ago, until a vaccine was developed and the disease was largely eradicated. Then last Friday, New York City health authorities announced that they had found the virus in wastewater samples, suggesting polio was probably circulating in the city again. www.nytimes.com/2022/08/12/nyregion/polio-nyc-sewage.html?

Parents of young children found themselves wondering — perhaps for the first time in their lives, and, collectively, for the first time in generations — just how much they should worry about polio.

In New York City, the overall rate of polio vaccination among children 5 and under is 86 percent, and most adults in the US were vaccinated against polio as children. Still, in some city ZIP codes, fewer than two-thirds of children 5 and under have received at least three doses, a figure that worries health officials.

The state Health Department said in a statement the discovery of the virus underscored “the urgency of every New York adult and child getting immunized, especially those in the greater New York metropolitan area.”

The announcement came three weeks after a man in Rockland County, N.Y., north of the city, was diagnosed with a case of polio that left him with paralysis. Officials now say polio has been circulating in the county’s wastewater since May.

The spread of the virus poses a risk to unvaccinated people, but three doses of the current vaccine provide at least 99 percent protection against severe disease.

Health officials fear that the detection of polio in New York City’s wastewater could precede other cases of paralytic polio.

The polio virus had previously been found in wastewater samples in Rockland and Orange Counties, but the announcement on Friday was the first sign of its presence in New York City.

A research team has developed a way to assess the gene activity of single cells that harbour latent HIV genes—a technique that could aid the search for a cure. People living with HIV who take existing antiretrovirals invariably retain infected cells that dodge drugs and natural immune responses. Even though scientists could identify these rare reservoir cells, technical constraints prevented them from evaluating the cells’ gene activity. The new method, revealed at the 24th International AIDS Conference last week, hinges on “microfluidic” devices that allow investigators to retrieve genetic material from the infected cells for sequencing. The team found that the reservoir cells had unique patterns of gene activity, turning on genes that protect them from immune attack and self-destruction. Targeting these genes could, in theory, reduce, if not eliminate, the HIV reservoirs.

///

Lalita Panicker is Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi