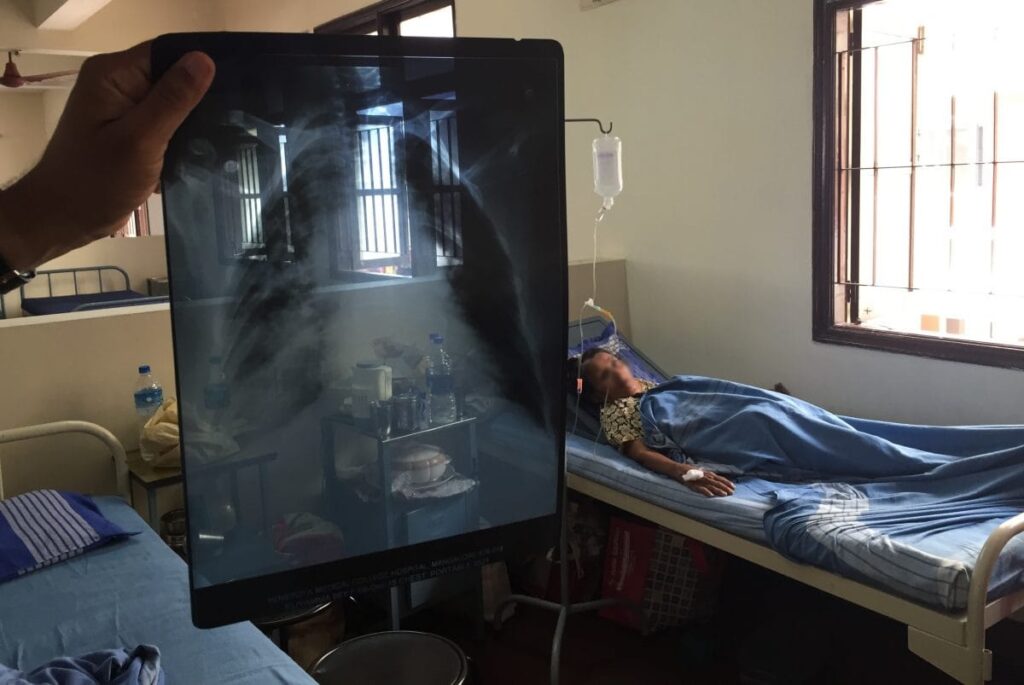

The pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson (J&J) in mid-July agreed to help make a therapy critical to fighting drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) more widely available and affordable. J&J said it would allow competitors to market generic versions of the lifesaving drug, bedaquiline, in 44 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the company has active patents. www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-ben-franklin-s-anticounterfeiting-science-s-english-language-barrier?

The United Nations–affiliated Stop TB Partnership’s Global Drug Facility, which announced the deal with J&J, now sells the drug in LMICs for $45 per month for a 6-month course; generic versions are estimated to cost $8 to $17 per month. The announcement came 2 days after bestselling fiction author John Green assailed the company on social media, claiming it made minor modifications to the drug to extend its patent protection in the 44 LMICs. J&J called that “false.” India’s patent office denied J&J a patent extension there in March. The expiration of a key J&J patent this week is expected to make generic versions available in dozens of additional LMICs.

////

On the heels of the historic full US approval of the Alzheimer’s therapy lecanemab, a similarly acting drug has also demonstrated some effectiveness against the brain disorder, albeit with potentially greater risks, according to detailed clinical trial data released 17 July by its maker, Eli Lilly and Co. www.science.org/content/article/alzheimer-s-trial-shows-clear-benefits-and-significant-risks-eli-lilly-antibody?

The experimental therapy, donanemab, is a monoclonal antibody that mops up a protein called beta amyloid, which accumulates in the brains of people with the disease and is associated with its progression. Both drugs appear to modestly slow the cognitive decline that marks Alzheimer’s, making them the first amyloid-targeting drugs to clearly demonstrate such success in advanced clinical trials.

Speaking at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Amsterdam, and publishing simultaneously in JAMA, Eli Lilly officials and scientists involved in testing donanemab followed up on bare-bones results released in early May, which reported that regular infusions of the antibody slowed the rate of cognitive decline as much as 35% compared with a placebo. This “is a positive trial,” said John Sims, head of the donanemab program at Eli Lilly, to thunderous applause during his presentation.

But both donenemab and lecanemab, marketed by Eisai and Biogen as Leqembi, come with risks of serious and even fatal brain swelling and bleeding. The positive trial results “would likely not be questioned by patients, clinicians, or payers if amyloid antibodies were low risk, inexpensive, and simple to administer,” wrote a trio of geriatrics specialists in a commentary accompanying the JAMA paper. “However, they are none of these.”

The pivotal donanemab trial enrolled 1736 patients across eight countries, who were randomized to get either the experimental antibody or a placebo. Both groups got intravenous infusions every 4 weeks for 18 months. Only 1320 of the participants completed the trial, 622 of whom were on the treatment; dropouts were attributed to side effects, changes in caregiver circumstances, and other reasons. In one criticism, outsiders noted the trial lacked diversity; more than 91% of the participants were white.

Although all the participants had symptoms of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and brain imaging confirmed they had amyloid build-up in the brain, the company slotted them into two different groups based on measures of a second brain protein called tau. Typically as the condition progresses, tau can malfunction inside neurons and form clumps. In general, scientists believe that having more such tau “tangles” indicates a more advanced stage of disease. Almost one-third of the trial participants were considered to have “high” tau pathology, based on positron emission tomography (PET) scans, and the rest had “low/medium” tau pathology.

Researchers expect anti-amyloid antibodies to work better in earlier stages of Alzheimer’s disease, and indeed, trial leaders found that donanemab’s power to slow cognitive decline was greater for participants with lower tau levels. Across all participants taking donanemab, there was an average 22% or 29% slowdown, depending on the cognitive test, roughly comparable to lecanemab’s effect. But the treated participants with low/moderate tau, who had a 35% or 36% slowdown in cognitive decline, pumped up that overall average.

One open question about anti-amyloid antibodies is whether people taking them must do so indefinitely, which has downsides because of cost, side effects, and the inconvenience and discomfort of infusions.

Eli Lilly’s trial experimented with discontinuing donanemab if a PET scan 6 or 12 months into treatment showed overwhelming clearance of amyloid plaques. About half of the participants in the low/medium tau group met this benchmark and were switched to infusions of a placebo (unbeknownst to them or the trial doctors caring for them). Their cognition didn’t decline any faster over the remaining time of the 18-month trial than the group that stayed on donanemab, suggesting it may be possible to shorten time on treatment or at least interrupt it, though study of this group continues.

A mix of celebration and caution is greeting Eli Lilly’s fuller data release, a reaction similar to that provoked by lecanemab’s data. Alzheimer’s has proved intractable and invariably fatal, and these two drugs are the first to definitively slow its cognitive decline, albeit modestly.

Donanemab appears to come with higher risks than lecanemab. As a class, anti-amyloid antibodies carry a chance of brain swelling and bleeding—known collectively as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA)—whose severity can range from asymptomatic to fatal. In the donanemab trial, almost 37% of people getting the antibody developed ARIA, although many had no symptoms—the condition only being detected by brain imaging. One-quarter of participants on donanemab had brain swelling, the more common form of ARIA, and about one-quarter of these patients had symptoms, which included headaches and confusion. Three people died from brain swelling or bleeding attributed to the treatment.

By contrast, 21% of those taking lecanemab in the phase 3 trial developed ARIA, and 12.6% had brain swelling; there were no deaths linked directly to the drug in the main phase 3 trial but three deaths have been attributed to it in an extension phase of the trial.

But comparing results across therapies is difficult because of differences in trial designs, notes Fabrizio Piazza, a translational researcher studying Alzheimer’s and ARIA at the University of Milano-Bicocca who was not involved in the trial. At the same time, such comparisons are irresistible, says David Knopman, a clinical neurologist at the Mayo Clinic who didn’t participate in the trial. “You can’t do it to the fourth decimal point,” he continues, but when it comes to effectiveness he believes the two treatments are “about the same.” The risks for donanemab certainly appear higher, he says—but that’s countered by the fact that infusions are every 4 weeks instead of every two, and that patients may be able to discontinue therapy as the trial suggested.

Eli Lilly has applied to FDA for approval of donanemab and says it expects a response by year’s end. It is currently enrolling people with amyloid build-up but no Alzheimer’s symptoms in another phase 3 trial. “There is a palpable excitement about what’s happening in our field,” said Maria Carrillo, chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, at today’s press conference. After decades without effective treatments, “this is a very big change for us.”

///

About 20% of people infected by SARS-CoV-2 don’t develop symptoms, and researchers have discovered one reason why: They are more than twice as likely as people who get sick to carry a particular version of HLA-B, a key immune system gene.

www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-ben-franklin-s-anticounterfeiting-science-s-english-language-barrier?

HLA-B codes for a cell-surface protein that alerts the immune system to invading viruses. The protective HLA-B variant may allow immune cells to purge infected cells rapidly and eradicate the virus before a person becomes ill, the scientists report this week in Nature. When they tested blood samples collected from people with this variant before the COVID-19 pandemic, they determined that 75% carried immune system T cells already primed to attack SARS-CoV-2, likely because of exposure to common coronaviruses, relatives of SARS-CoV-2 that cause colds. The HLA-B variant doesn’t explain all asymptomatic COVID-19 infections—only 20% of people in the study who remained symptom-free carried it. But the result could help researchers refine COVID- 19 vaccines and develop new treatments.

////

A clinical trial of a personalized cancer vaccine, mRNA-4157, has caused a surge of excitement about the technology. “It’s the best proof-of-principle that the field could have,” says oncologist Ryan Sullivan, who was involved in the trial, run by US pharmaceutical company Moderna. In the study, 107 people with high-risk melanoma were given mRNA-4157 in addition to the checkpoint-inhibitor drug pembrolizumab, and 50 were treated with pembrolizumab alone. After 18 months, the people

who received the vaccine had a 44% lower risk of death or relapse compared with those in the pembrolizumab-only group. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery | 12 min read Reference: Association for Cancer Research annual meeting abstract (April) /// Researchers have coaxed cancer cells from mice and humans into becoming dendritic cells, which can recruit the immune system to fight cancer by displaying tumour molecules called antigens on their surface. The transformation was prompted by transcription factors PU.1, IRF8 and BATF3, which are proteins. Mice with tumours were injected with the modified cancer cells; their tumour growth slowed and the mice lived longer than mice given a placebo. The technique could form the basis of a new type of immunotherapy.

Reference: Science Immunology paper (7 July)

///

Lalita Panicker is Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi