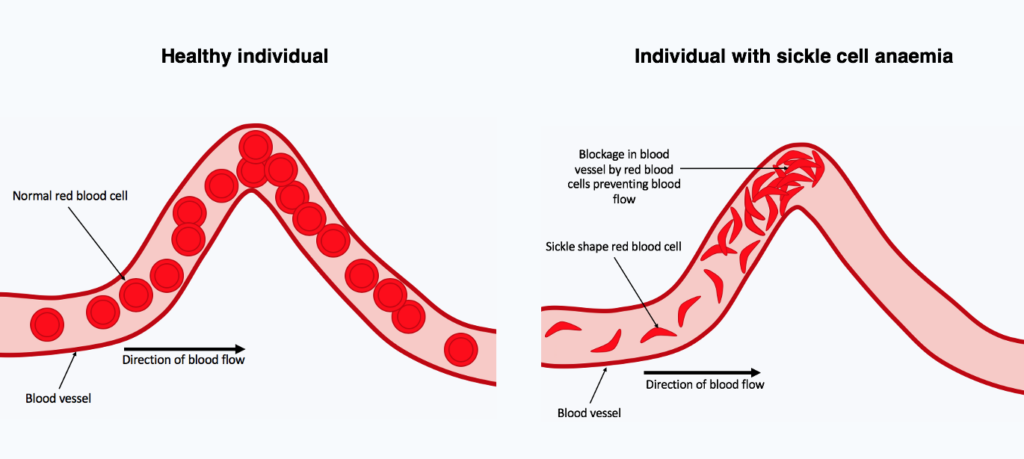

In a world first, U.K. regulators have approved a therapy that uses CRISPR, the Nobel Prize–winning gene-editing tool invented in 2012. The treatment has been shown to help people with beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease, both inherited blood disorders that involve defects in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin. It relies on removing blood stem cells from patients, using CRISPR to turn on the gene for a foetal form of haemoglobin, then reinfusing the cells. https://www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-new-cancer-institute-head-nih-s-applied-research-tilt-and-bias-free

The therapy, developed by the companies Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics, has been tested in clinical trials with dozens of patients. Almost all those with sickle cell stopped having debilitating pain “crises,” and most beta thalassemia patients were able to forgo the blood transfusions they previously needed. The treatment is expected to cost at least $2 million, raising questions about whether the UK’s National Health Service and U.S. insurance companies will cover it. U.S. regulators are expected to approve the therapy for sickle cell disease by 8 December and for beta thalassemia by 30 March 2024.

///

President Joe Biden has tapped Vanderbilt University Medical Centre physician-scientist Kimryn Rathmell to direct the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI). Rathmell has helped lead large projects to sequence tumour genomes, and her work on the biology of kidney cancer has led to new ways to treat the disease. Biden called her a “talented and visionary leader” who “embodies the promise of the Biden Cancer Moon-shot,” his effort to halve the death rate from cancer by 2047. She will replace Monica Bertagnolli, who headed NCI for just over a year before the U.S. Senate confirmed her this month as director of its parent agency, the National Institutes of Health.

/////

When thousands of cats started to die this year on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, nicknamed the “island of cats” for its 1-million-strong feline population, the crisis made international news. The animals had fevers, swollen bellies, and lethargy—symptoms that pointed to feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a common condition caused by a type of cat coronavirus. But scientists struggled to explain the apparent explosion in cases. https://www.science.org/content/article/new-feline-coronavirus-blamed-thousands-cat-deaths-cyprus

Now, researchers have identified a possible culprit: A new strain of feline coronavirus that has co-opted from a highly virulent dog pathogen called pantropic canine coronavirus (puccoon). The findings, posted as a preprint last week on bioRxiv, could help explain how severe illness managed to spread so widely among cats on the island.

“They’ve done a great job in identifying what looks to be a very interesting and concerning virus,” says Gary Whittaker, a virologist at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine who was not involved in the research. Although canine-feline coronavirus crossovers have been reported before, he says, this is the first documented case of a cat coronavirus combining with pCCoV, apparently leading to a “perfect storm of both disease and transmissibility.”

Veterinarians in Cyprus raised the alarm early this year about increased cases of FIP, which is not related to COVID-19 and does not affect humans. By July, animal activists and media outlets had reported nearly 300,000 deaths, although local veterinarians revised that figure dramatically downward, to about 8,000. In August, the Cypriot government agreed to the veterinary use of the human SARS-CoV-2 medication molnupiravir, which blocks coronavirus replication and appears to be an effective treatment for FIP.

The rapid rise in cases presented scientists with a puzzle. Most feline coronaviruses infect the gut, where they cause mild infections that don’t escalate to FIP. These strains are easily transmitted from cat to cat through faeces. They sometimes mutate into a more dangerous form called FIP virus (FIPV) that instead infects immune cells and triggers serious disease. But unlike the intestinal strains, FIPV typically isn’t transmitted between animals.

To determine what was causing the new infections, researchers at the University of Edinburgh and colleagues collected fluid samples from the abdomens and spines of sick cats admitted to clinics in Cyprus and used RNA sequencing to look for viral genetic information. What they found was a previously undescribed feline coronavirus, which they dubbed FCoV-23, that contains a large chunk of RNA from the dog virus pCCoV. (The “pantropic” in its name means that, unlike regular intestinal canine coronaviruses, pCCoV infects lots of different tissues.)

FCoV-23 appears to have arisen when a feline coronavirus encountered pCCoV in an unidentified animal host and co-opted the latter’s spike protein—the structure coronaviruses use to gain access to host cells, explains study co-author Christine Tait-Burkard, a virologist at the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute. This and other genetic tweaks may have allowed FCoV-23 to cause severe FIP while still infecting the intestines and spreading through faeces, she says. The team also speculates that the spike protein changes could have made FCoV-23 more stable outside an animal host, increasing the chance of transmission via contact with contaminated faeces.

It’s not yet clear how far FCoV-23 has spread, although the team did identify one case in the United Kingdom in a cat that had been imported from Cyprus. The general risk to cats outside the island remains low, Tait-Burkard says.

Margaret Hosie, a virologist at the University of Glasgow and president of the European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases, says it’s exciting to see virological data emerging from the Cypriot population.

The apparent rise in FIP cases this year could partly be the result of increased awareness of the condition, she notes. “We don’t know the numbers previously, so we can’t say there’s been a huge outbreak.” Feline coronaviruses and pCCoV have coexisted in the Mediterranean region for years, she adds, so it’s possible that the genetic crossover happened some time ago.

In the meantime, the discovery of this mixed cat-dog coronavirus highlights the importance of taking a broad, cross-species approach to understanding viral evolution, Whittaker says. “This feline coronavirus has got huge potential for us to understand what goes on in general in coronavirus virology.”

/////

An obesity drug called Zepbound has won approval for use in adults from the US Food and Drug Administration, ushering in a new rival to Novo Nordisk’s blockbuster Wegovy. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/11/08/1211583497/fda-approves-zepbound-a-new-obesity-drug-that-will-take-on-wegovy?

Eli Lilly & Co., maker of Zepbound, says it shows greater weight loss at a lower list price than Wegovy. The Lilly drug will be available in the U.S. by the end of the year. A version of the shot, known generically as tirezepatide, is already sold as Mounjaro to treat Type 2 diabetes.

The Lilly drug works by acting on two hormone receptors in the brain, including one called GLP-1, short for glucagon-like peptide-1 – that regulate appetite and metabolism.

The new class of medicines for managing obesity that includes Zepbound and Wegovy has given people with obesity and overweight a potent option for treatment. But the drugs are expensive, and many people who lose weight regain it after stopping the medicines.

In clinical trials, the average weight loss for people taking Zepbound was about 20%. One in three users of the medication at its highest dose, saw weight loss of about a quarter of their body weight. The results are roughly equivalent to those of bariatric surgery.

Common side effects from the drug include nausea, diarrhoea, constipation and vomiting. The drug also caused thyroid tumours in rats, though the FDA said it’s not known if Zepbound causes the same kind of tumours in humans.

In announcing the approval, the FDA cited the growing public health concern over excess weight. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need,” said Dr John Sharretts, director of the Division of Diabetes, Lipid Disorders, and Obesity in the FDA’s Centre for Drug Evaluation and Research. About 70% of adult Americans are obese or overweight, the FDA noted.

“New treatment options bring hope to the many people with obesity who struggle with this disease,” said Joe Nadglowski, president and CEO of the Obesity Action Coalition, in a statement released by Lilly. He noted numerous life-threatening diseases — from heart attacks and strokes to diabetes — that are linked to obesity.

New medications to treat obesity and related conditions have become wildly popular, but are expensive, especially when paid for out of pocket.

Lilly said people with commercial health insurance that covers Zepbound “may be eligible to pay as low as $25” for one-month or three-month prescriptions.

Lilly will offer a discount card to help defray the expense for people who have commercial health insurance that doesn’t include coverage for the drug. The cost could be reduced to $550 for a one-month prescription of Zepbound, or about half the list price, Lilly said.

Medicare doesn’t pay for weight-loss drugs. However, Congress is considering measures that would expand insurance access to cover treatments for obesity, including some of the new medications, for Medicare enrollees.

////

Lalita Panicker is Consulting Editor, Views and Editor, Insight, Hindustan Times, New Delhi